Description

America’s First Highway Venture: The National Road

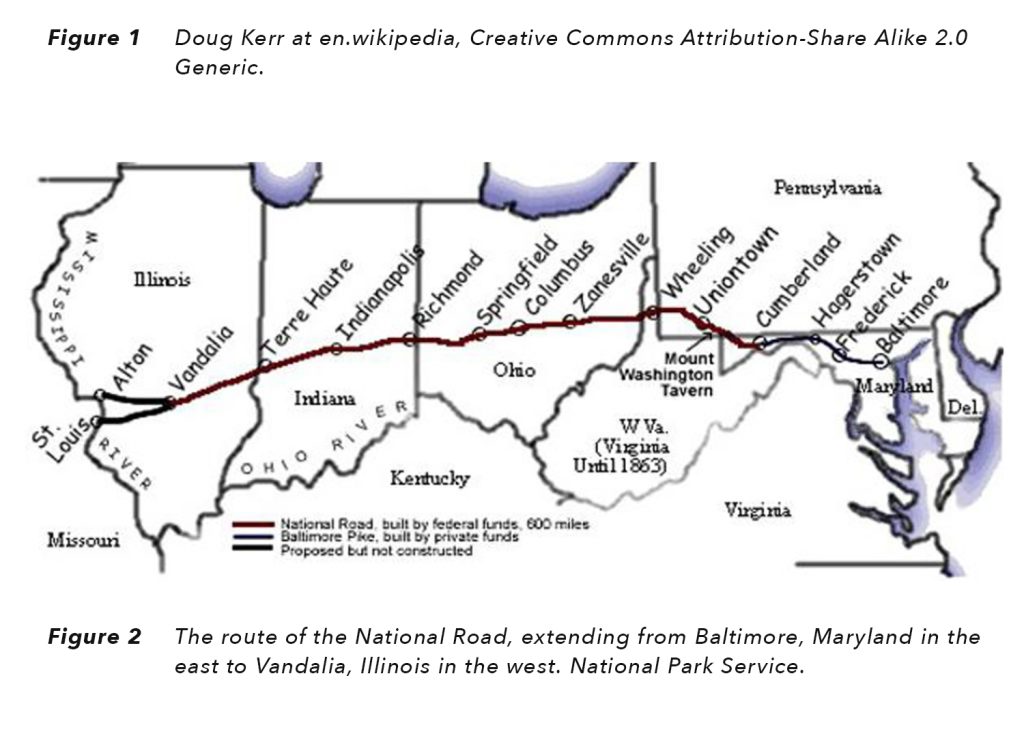

The National Road (also known as the Cumberland Pike or Cumberland Turnpike) was the first American highway funded by Congress. President George Washington was among those who early on saw the value of a highway, one that would lead from Maryland, the center of the United States at that time, westward to Ohio and beyond. Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, became a strong proponent during the administration of President Thomas Jefferson. Following Congressional action, Jefferson signed an initial $30,000 allocation on March 29, 1806, Henry McKinley received the initial contract on May 8, 1811, and construction began later that year. As originally conceived, its 620-mile path began at the edge of the Potomac River in Cumberland, MD, reached Wheeling, VA (now WV) in 1818, and extended to the Kaskaskia River in Vandalia, IL in 1841.

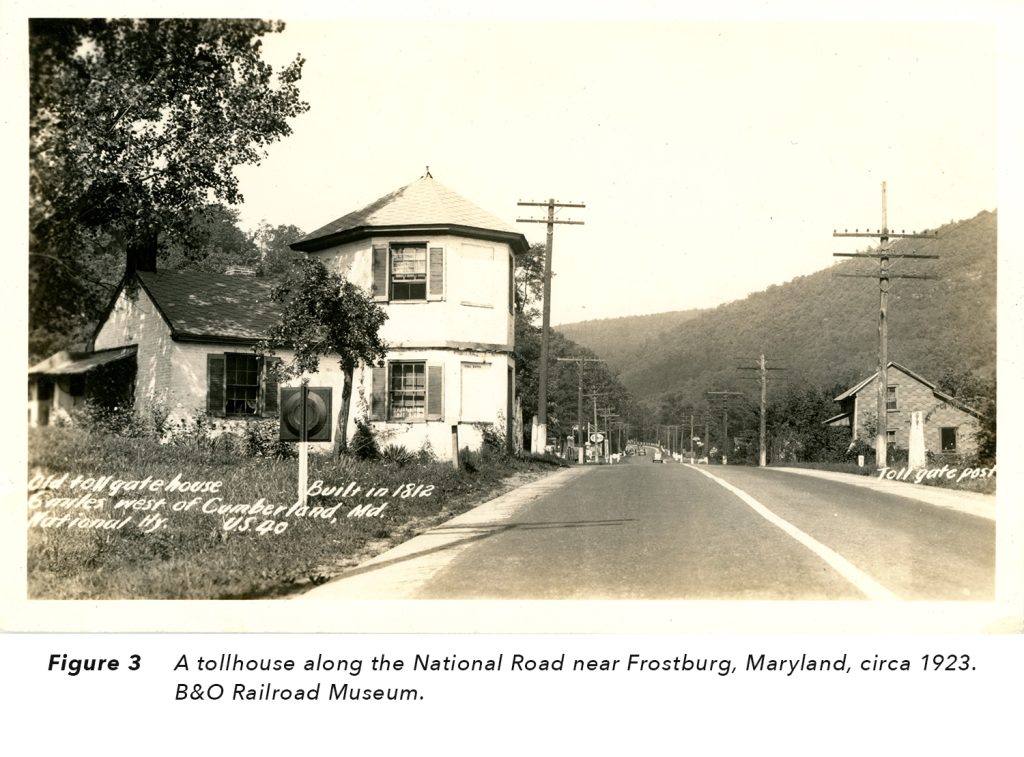

Although Congress approved an extension to St. Louis on the Mississippi River and then west to Jefferson City, MO on May 15, 1820, the final federal appropriation occurred on May 25, 1838, and construction short of completion concluded in 1839. By 1840, Congress voted against completion of the road, consistent with an 1835 federal decision to transfer future construction and maintenance costs to the states through which the highway passed. The states then introduced tolls and tollbooths to cover maintenance costs.

As shown in the map (Figure 2), descriptions of the National Road today show the road beginning in Baltimore, 118 miles to the east of Cumberland. A series of private toll roads (known as the Old National Pike or the Baltimore Pike) offered Improved travel between those two communities before authorization of the National Road. Over time, the entire highway from Baltimore to Vandalia, IL gained recognition as the National Road.

Proponents outside and within Congress believed that a National Road warranted federal funding for two principal reasons — population growth and economic development. The US Census for the decades beginning from 1790 to 1800 and then to 1810 showed increases in population exceeding 33% in each decade. In addition, Americans were rapidly moving west. Ohio was admitted to the Union in 1803, followed by Indiana (1816) and Illinois (1818). Economically, there was an ever-growing need for goods produced or imported by the major cities of Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York to reach and meet the necessities of those living on the western frontier. Equally strongly, the goods generated in the newly developed western farms and towns needed to reach those living along the Atlantic coast.

The route of the National Road initially followed paths and trade routes extending as far back as the French and Indian War (1753-1763). Named for British General Edward Braddock, the so-called Braddock Road led from Fort Cumberland in Maryland to Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh, PA) during that period. Additional surveying led to route modifications and improvements throughout the life of the National Road.

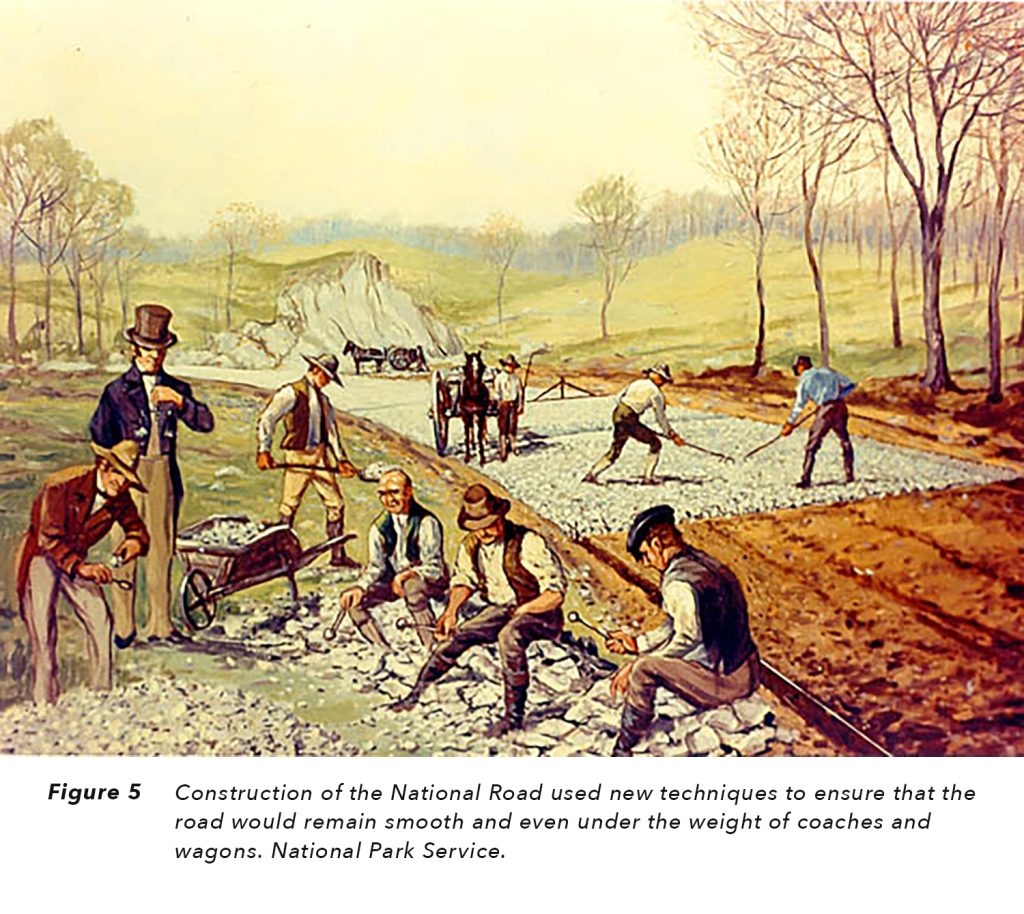

At the time of planning for the National Road, the great difficulty of all travel routes west was their lack of hard surfaces. The result was constant deep and troublesome ruts from the wheels of heavily loaded wagons and stagecoaches. The National Road builders introduced new techniques to avoid those problems. (Figure 5) The road was wide enough to permit wagons and coaches to pass each other from opposite directions and banked so that water would easily drain to the sides. Stone markers recorded distances to the east and west. More significantly, the builders introduced a new construction method, borrowing the thinking of British engineer, John Louden MacAdam. William Cobbett, a British writer who visited a construction site on the National Road in 1817, described the construction method:

“It is covered with a very thick layer of nicely broken stones, or stone, rather, laid on with great exactness both as to depth and width, and then rolled down with an iron roller, which reduces all to one solid mass. This is a road made for ever.”

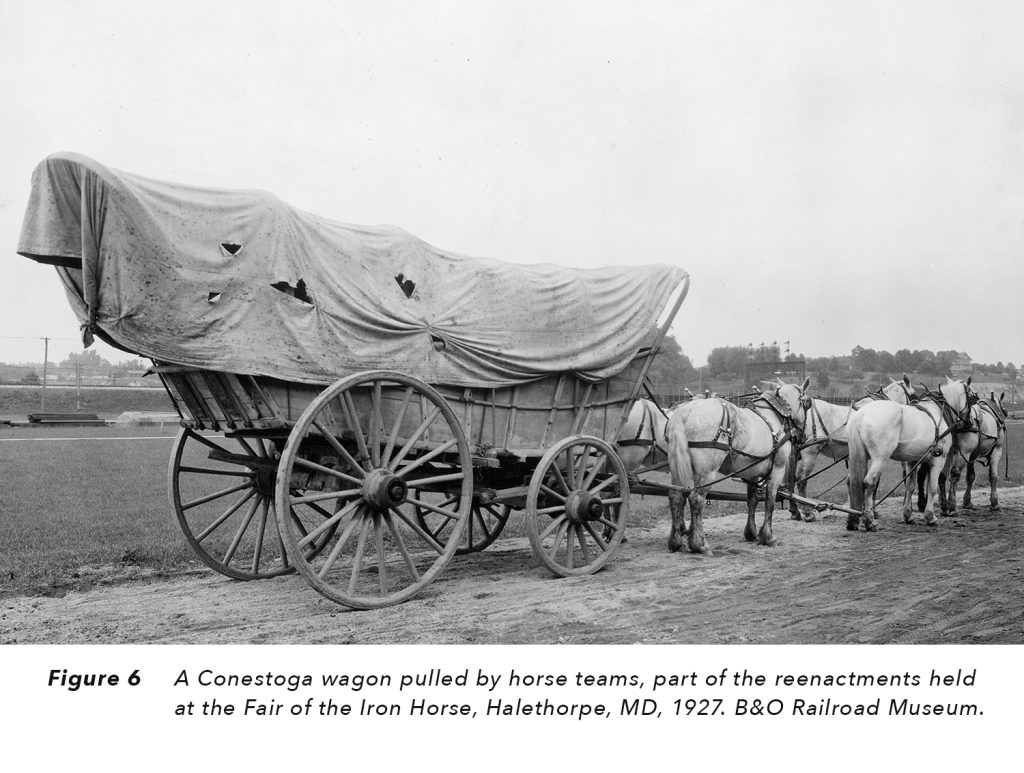

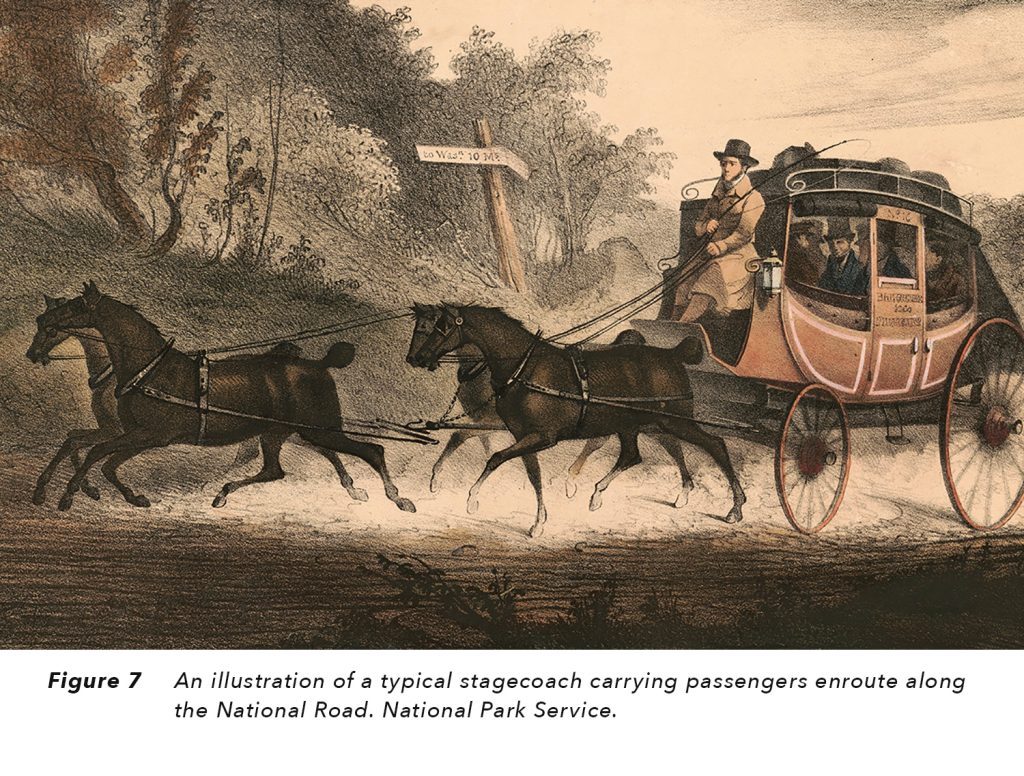

Traveling on the National Road was primarily by stagecoach and lumbering Conestoga wagons. Stages were for speedy passenger travel and might average 60 to 70 miles per day. Conestoga wagons were the “tractor trailers” of the 19th century and averaged fifteen miles per day. (Figure 6 & 7)

Serving travelers, wagoneers, coachmen and their vehicles and horses were the taverns providing lodging, food, and beverages. Some have suggested that there was a tavern for every mile of the road. “Stagecoach taverns” served the more affluent travelers; others found the more affordable “wagon stands” to be satisfactory. (Figure 8)

The National Road reached its height in popularity by 1825 and continued as the principal means of reaching the western frontier into the 1840’s. However, by the early 1850’s, use of the National Road diminished because of the westward growth of the steam powered Baltimore & Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroads which moved people and goods much faster than horse-drawn vehicles.

“An account published in the late 1800’s recalled the glory days of the National Road

There were sometimes twenty gaily painted four-horse coaches each way daily. The cattle and sheep were never out of sight. The canvas-covered wagons were drawn by six or twelve horses. Within a mile of the road the country was a wilderness, but on the highway the traffic was as dense as in the main street of a large town.”1

“An article in Harper’s Magazine in 1879 declared

The national turnpike that led over the Alleghenies from the East to the West is a glory departed . . . Octogenarians who participated in the traffic will tell an enquirer that never before were there such landlords, such taverns, such dinners, such whiskey . . . or such endless cavalcades of coaches and wagons” 2

“A poet lamented,

We hear no more the clanging hoof and the stagecoach rattling by, for the steam king rules the traveled world, and the Old Pike is left to die” 3

Many miles of the route, bridges and sites associated with this first nationally funded interstate highway remain today. After declining in use due to the innovative technology of the railroad, it regained a place in American history with the still later technology of the automobile. Autos led to the growing interest of Americans in “motor touring” to historic sites and national parks for vacations.

In response to this growing interest in auto travel, the US established the first national highway numbering system in 1926. Much of the eastern portion of the National Road extending from Baltimore into Ohio became the new US Route 40. A year later, the National Old Trails Road described an early cross-country route extending from New York City to Los Angeles. It also followed a portion of the path of the old National Road.

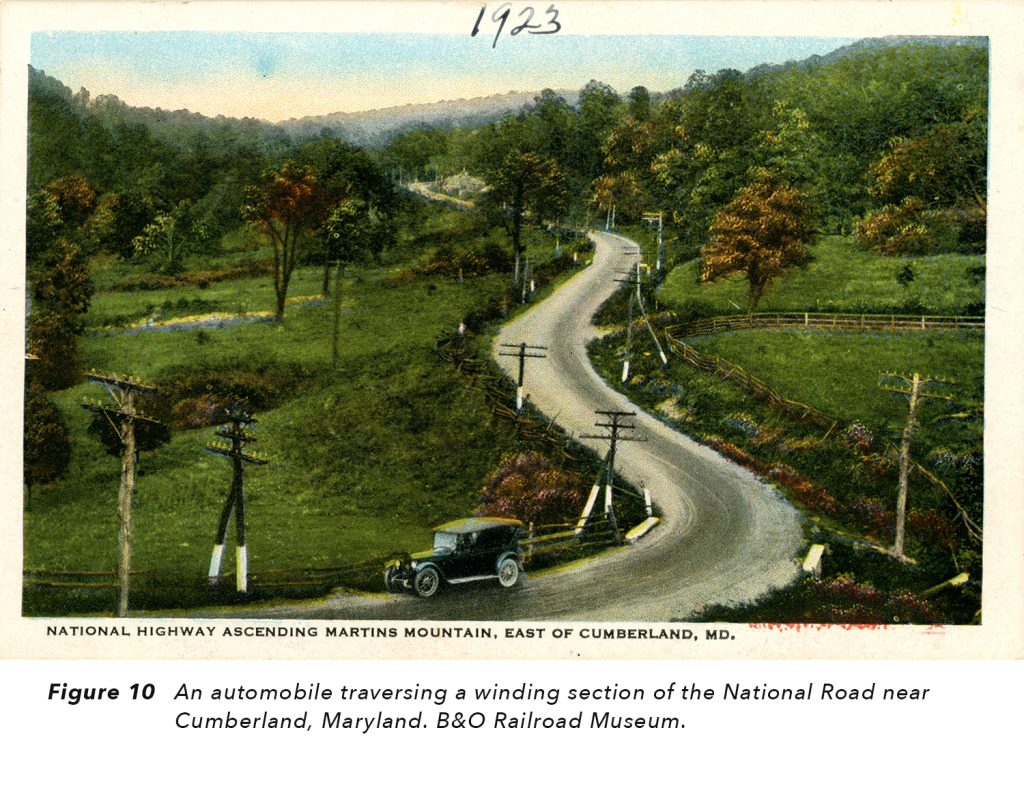

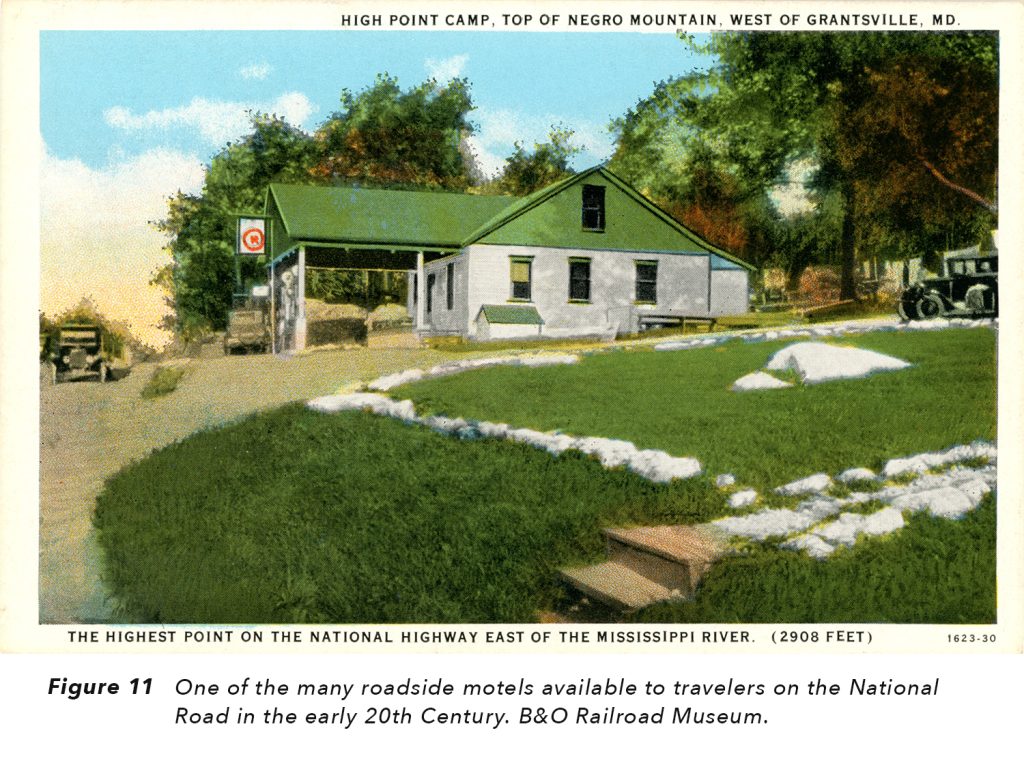

These photographs (Figure 9-11) show 1920 Americans traveling east and west on US Route 40 through the hills and valleys of Maryland. They were following the familiar, “Happy Motoring” slogan of Esso Oil.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Road

https://nationalrdfoundation.org/

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/back0103.cfm

https://www.nps.gov/fone/learn/historyculture/nationalroad.htm

https://www.nps.gov/articles/national-road.htm

https://www.google.com/search?source=univ&tbm=isch&q=National+Road&client=firefox-b-1-d&fir=jpyz35k4BWugEM%25252CJOT49t

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ah-nationalroad/

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/cumberland-road

https://study.com/academy/lesson/national-road-definition-history.html

https://www.thoughtco.com/the-national-road-1774053

John Geist, Archives Volunteer, and Anna Kresmer, Archivist, December 2022

Can't Get Enough?

There’s even more to explore. Check out this and other unique pieces from our collection.

Did You Know?

Railroads made possible the standardization of time in the United States.